Pope St. John Paul II’s 1998 Fides et ratio was the first encyclical since Pope Leo XIII’s Aeterni Patris (1879) to deal explicitly with the relationship between faith and reason. Both emphasized that faith and reason are not opposed, but represent two paths to the same truth.

The Pope’s successors have confirmed the teachings of Fides et ratio. Pope Francis writes, for example, that “The Catholic Church is open to dialogue with philosophical thought; this has enabled her to produce various syntheses between faith and reason” (Laudato si’, 63).

The encyclical was translated into Norwegian by Anne Krohn and published by St. Olav forlag in 2008, but the translation has not been available online until now.

The encyclical Fides et ratio in Norwegian

In short

- Gregory Reichberg is a philosopher and researcher at PRIO, as well as a member of the Vatican’s Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences.

- He has a personal connection to the encyclical Fides et ratio through his former professor, Cardinal Georges Cottier, who had a significant role in drafting the document.

- The encyclical raises important questions about meaning and truth and warns against relativism and nihilism, among other things.

- Reichberg relates the themes of the encyclical to today’s challenges of artificial intelligence and purely instrumental reason.

- He believes that philosophy is crucial to faith and societal deliberation, and that the lack of a shared basis of truth leads to polarization.

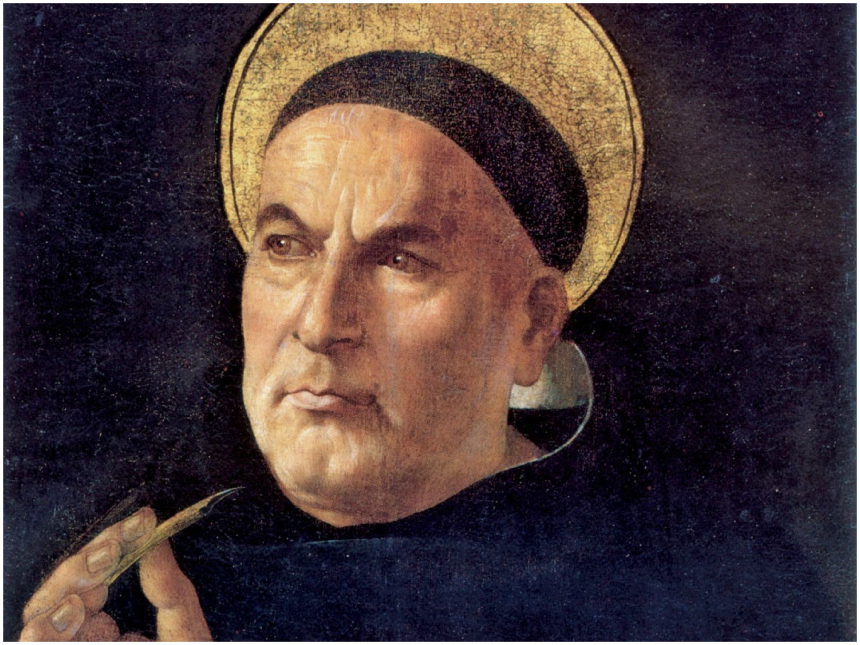

- The Pope highlights Aquinas as an important thinker, and Reichberg recommends his works for those who want to reflect on the relationship of faith and reason.

Knew the man behind it

Gregory Reichberg is a philosopher, a researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and a member of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences. He has recently re-read the encyclical Fides et ratio for the first time since its publication, and has a personal connection to it.

From his office in Oslo, he says that one of his professors while studying philosophy in France was Cardinal Georges Cottier (1922–2016), the Pope’s “house theologian,” who contributed to drafting the encyclical.

Gregory, who uses the short form Greg, walks over to one of his large bookcases and picks out a book by Cardinal Cottier entitled Humaine raison: Contributions à une éthique du savoir (Human Reason: Contributions to an Ethics of Knowledge).

The book bears a handwritten greeting to him from the cardinal, “in recognition of our long-standing friendship.”

― A lot of the encyclical is also about the ethics of knowledge, and I can see his (Cottier’s) thinking behind many of the lines: How to make good use of the human mind, both socially and personally, applying it in ways that are conducive to human flourishing and avoiding traps that lead us away from that flourishing, Greg says.

Relevance of the encyclical

Foto: Paul Ronga (CC BY 3.0)

Greg Reichberg points out that Fides et ratio appeared in the 1990s, a period of relative stability and prosperity (at least in the West), when people were pushing aside questions of deeper meaning and filling their lives with more and more material goods. Now that we have entered a period of great instability, these sorts of questions arise for more people in a more pressing way.

― In what ways is the encyclical still relevant today?

― At the very outset, it situates the topic of faith and reason within the context of the search for meaning, which is characteristic of the human being. When you scratch below the surface, everyone—including non-believers—has questions about life and death. Not just about my own personal demise, but about the radical contingency of our collective existence on earth: If it is all going to end, what is the point of what we do?

Pope St. John Paul II makes it clear that such questions are a good thing and that the Church should not be afraid of them. Faith is ultimately an answer to questions that people ask. He warns against voices that say it is impossible to find answers. Such views discourage man’s search for meaning because they portray it as futile.

Not just about my own personal demise, but about the radical contingency of our collective existence on earth: If it is all going to end, what is the point of what we do?

― One of the orientations mentioned in the encyclical is pragmatism or the technological use of a purely instrumental reason: You don’t value reason to grasp the truth, but you cultivate it solely to serve utilitarian purposes—to accomplish things in the world. Ultimately this is embedded in a project to achieve mastery over nature, but paradoxically human beings themselves end up in bondage when you “absolutize” this approach, says Greg.

Pope St. John Paul II quotes from his first encyclical, Redemptor hominis: “The man of today seems ever to be under threat from what he produces, that is to say from the result of the work of his hands” (Fides et ratio, 47).

Pope Francis has addressed something similar: “Hence we should not be surprised to find, in conjunction with the omnipresent technocratic paradigm and the cult of unlimited human power, the rise of a relativism which sees everything as irrelevant unless it serves one’s own immediate interests” (Laudato si’, 122).

― When you cut yourself off from a higher (non-instrumental) reason, you are no longer able to assess the good or bad use of what you have made. That is what is happening today with artificial intelligence, which is an expression of purely instrumental reason, says Greg.

He describes the use of artificial intelligence (AI) as part of a program of personal and societal self-actualization, where the goal is to have a technology that can do our thinking for us and carry out most work tasks for us.

When you cut yourself off from a higher (non-instrumental) reason, you are no longer able to assess what is good or bad use of what you have created.

― The Pope also writes about the political implications of nihilism: What happens when we don’t believe in reason any more? Then there is nothing objective we can point to in order to organize collective action. In this way, nihilism leads to polarization, and we end up with a set of competing statements that must be evaluated in the absence of a shared basis of truth. It turns politics into just a power struggle.

The encyclical points not only to misconceptions of reason, but also to misconceptions of faith as dangerous. Among these is fideism, which “fails to recognize the importance of rational knowledge and philosophical discourse for the understanding of faith” (Fides et ratio, 55). Greg describes this as thinking about faith in terms that make it unable to interact with reason.

― What about what the Pope says about relativism?

― What I like about the encyclical is that it keeps a positive tone throughout. It attempts to explain how the various orientations that are detrimental to truth-seeking all have a kernel of truth that we need to recognize. Relativism comes from a recognition of how difficult it is to search for truth. This is not easy.

In a sense, human reason, as exercised by humans, is a wounded reason... If the human mind is left entirely to itself, it is very difficult to see clearly—especially when it comes to the big questions.

Greg refers to a passage in which the Pope writes about the dangers of thinking that the search for truth is easy: “The philosopher who learns humility will also find courage to tackle questions which are difficult to resolve if the data of Revelation are ignored—for example, the problem of evil and suffering, the personal nature of God and the question of the meaning of life,” and so on (Fides et ratio, 76).

― This is where faith comes into play. The Pope writes that reason as we know it needs to be healed. Human reason, as exercised by human beings, is a wounded reason (because of original sin). If the human mind is left on its own, it is very hard to see clearly—especially when it comes to the big questions.

This can make human reason more humble, but Greg points out that it can also make reason more hopeful.

― The truths we know through faith are considered certain. We know them because God tells us that it is so. This can make us want to know more about these truths, to understand them better. It also gives us hope that maybe we can reach some of these truths through another path, namely reason.

In this way, faith, rather than being a kind of conclusion or the end of a thought process, can become a new beginning that stimulates reason to further thought. This is the meaning of the phrase «faith seeking understanding» (fides quaerens intellectum).

― Relativism and the notion that we cannot rise above the level of opinion stems from a sense of discouragement. The insights we gain from God through faith can give us greater confidence to pursue the big questions philosophically—confident that answers can be reached.

Intellect and revelation

“Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth; and God has placed in the human heart a desire to know the truth—in a word, to know himself—so that, by knowing and loving God, men and women may also come to the fullness of truth about themselves.”

This is how Pope St. John Paul II begins his encyclical on faith and reason. Some would say that faith and reason are opposed, but this is a view the Pope clearly rejected: “It is the one and the same God who establishes and guarantees the intelligibility and reasonableness of the natural order of things upon which scientists confidently depend, and who reveals himself as the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ” (Fides et ratio, 34).

― What are faith and reason, and how do they relate to each other?

― First, both refer to acts of the human mind. Other aspects of Christian teaching—charity, for instance—refer not directly to the mind or intellect, but to the will. What is characteristic of faith and reason is that they are both activities of a capacity of the soul we call intellect (intellectus), says Greg Reichberg.

If you see faith solely as an affect or feeling linked to confidence, it becomes difficult to understand both the nature of faith and the possible union of faith and reason.

He points out that this is important to emphasize because people often talk about reason as an expression of the thinking part of the human being, while faith is often seen as an expression of the non-thinking part.

― If you see faith solely as an affect or feeling linked to confidence, it becomes difficult to understand both the nature of faith and the possible union of faith and reason, he says.

According to Thomas Aquinas (born 1224 or 1225, eight hundred years ago this year), faith is a source of insight. In this respect it is similar to reason. But while what we know by reason comes to us through sense experience, we cannot gain insight into the truths of faith in such a way.

― This inability is not due to the imperfection of faith. It is because the truths that we know through faith are perfect and utterly transcend human reason. What we know through faith is essentially the inner life of God. This is a truth so rich, so perfect, that the human mind is unable to grasp or comprehend it.

To believe means “holding something to be true on the word of another.” ... It is much better to understand something by experiencing it directly than through the word of another. This is how we will understand the truth of God in heaven (the “beatific vision”).

Greg explains that God provided a remedy so that we would not go astray: The one who has knowledge of God’s inner life, namely God himself, shares this highest truth with us as a teacher would share knowledge with a student. This is what we call God’s revelation.

― In school, you learn many things of which you have no direct experience, where you have to rely on the word of your teacher. This provides an analogy for the faith we have in God. To believe means “holding something to be true on the word of another.” Aquinas said that in this life we are in the condition of learners, but in the next life we will be in the condition of knowers. The knowledge of God we have in this life is imperfect. It is much better to understand something by experiencing it directly than through the word of another. This is how we will understand the truth of God in heaven (the “beatific vision”).

However, we should not devalue the knowledge of God that is available to us in this life, he says. It gives us access to truths that we would not otherwise have known. Our happiness as human beings is bound up with knowing these truths. He also points out that knowledge is a condition for love, because you can only love what you know.

The importance of philosophy

Pope St. John Paul II emphasises the importance of philosophy in the search for meaning and truth, although he also recognizes the natural sciences. Greg Reichberg points out that science in the broad sense includes philosophy, and that the Church sees all pursuit of truth as its natural ally. It is by no means opposed to science.

There is, however, a problem with so-called scientism, thinking that scientific reasoning must be the norm for all forms of reasoning: “In the past, the same idea emerged in positivism and neo-positivism, which considered metaphysical statements to be meaningless. Critical epistemology has discredited such a claim, but now we see it revived in the new guise of scientism”(Fides et ratio, 88).

Greg also points to the utilitarian turn as a problem, because the goal is no longer truth, but mastery over nature.

― What is it that makes philosophy so important?

― Philosophy in the narrow sense is a subject taught in universities. Philosophy in a broad sense is the human search for meaning in life. Without philosophical reflection, it can be difficult to embrace faith, because faith comes to us as an answer that God gives. Every answer presupposes a prior question. So philosophy has a vital role to play in preparing the way to faith.

According to the Pope in the encyclical, “All men and women ... are in some sense philosophers and have their own philosophical conceptions with which they direct their lives. In one way or other, they shape a comprehensive vision and an answer to the question of life’s meaning” (Fides et ratio, 30).

The Church sees it as of vital importance to maintain a philosophical culture… that engages on issues of metaphysics. This has a crucial cultural significance and is important for the maintenance of faith.

Greg emphasizes the importance of preserving what he calls a “philosophical culture,” not least through the teaching of philosophy—both in higher education, in Catholic schools and in the formation of priests in seminaries.

― If you were to remove philosophy (from curricula), a vital pathway to faith will be lost. If Catholics are not exposed to philosophy as they come into adulthood, their access to the faith is going to be weakened. The Church sees it as crucially important to maintain a philosophical culture. Not one that is highly specialized, but a culture that engages issues of metaphysics. This has a fundamental cultural significance and is important for the maintenance of faith.

Philosophical arguments

Pope St. John Paul II refers to the First Vatican Council’s (1869–1870) declaration that “the natural knowability of the existence of God, the beginning and end of all things” is “presupposed by Revelation itself” (Fides et ratio, 53).

Certain truths, such as the existence of God, can be known through both faith and reason and are sometimes called “preambles of faith” (praeambula fidei).

Saint Thomas Aquinas describes his arguments for God’s existence as “five ways” to God. According to Greg Reichberg, one should therefore not think of them as hard proofs, but as trajectories of thought that show that faith in God is not opposed to reason. He thinks it is valuable that people know what the terms of these arguments are.

― Do philosophical arguments have a role to play in the Church's encounter with the world today?

― Absolutely. One of the characteristics of our time is that we live in pluralistic societies. But we cannot each just do our own solitary thing. So it’s important that we can appeal to truths that do not depend on the special beliefs of a religious grouping: This is where reason becomes fundamental as a shared basis for discussions between different points of view (including different faith traditions).

In a society built on fideism on the one hand and secularized reason on the other, avenues for societal deliberation and agreement on what should be done are cut off.

Greg thinks it is a good thing that universities in Norway have what is called examen philosophicum (a required course in philosophy for all university students). In this way, many of the country’s intellectuals have been exposed to philosophy and structured ways of thinking about big questions. He contrasts this with the current situation in the USA, for example.

― In a society built on fideism on the one hand and secularized reason on the other, avenues for societal deliberation and agreement on what should be done are cut off. You end up with polarization, a condition where people cannot talk to each other in meaningful ways. That is where relativism and nihilism come in.

Recommended reading

Pope St. John Paul II highlights Thomas Aquinas as “a master of thought and a model of the right way to do theology” (Fides et ratio, 43). At the same time, he makes it clear that Aquinas is not the “official philosopher” of Catholicism, and that the Church is open to truths from other philosophers and schools of thought.

― Where should one begin to learn more about Thomas Aquinas?

― The challenge in reading Aquinas is the Aristotelian terminology that many are not accustomed to today. A book that is a good starting point is his Compendium theologiae. There exists a fine Norwegian translation by Nils Heyerdahl (Teologisk håndbok). It covers a lot of the same ground as the Summa theologiae, but in a much more succinct way.

According to Greg Reichberg, you may also want to skip the more densely theological first part of Summa theologiae and read the questions about the virtues (in secunda secundae, the second part of the second part). They begin with faith, hope and charity.

― You quickly get into matters that are more existential for us, about the nitty gritty of human life: dealing with fear, passion, envy and so on. He even talks about virtuous relaxation: you need to be able to rest the mind, and do it in constructive ways! That is something we are all dealing with in today’s world, with burnout and so on.

When you get to know Thomas, you can use him as a reference work and look up places where he might address questions you are wondering about.

See Summa theologiae II-II (the second part of the second part), question 168, article 2 to read about Aquinas’ views on the importance of rest and recreation. Greg tells us that he himself enjoys reading novels, which he describes as examples of “lived philosophy.”

― When you get to know Thomas, you can use him as a reference work and look up places where he might address questions you are wondering about. For example, I was working on issues around nuclear deterrence, which is a kind of threat. Naturally Aquinas didn’t talk about nuclear deterrence, but did he discuss about threats anywhere? In the end, I realized that he talks about it most directly in his treatment of oaths and vows, because a threat is a particular kind of promise.

Greg points out that there are several authors who can provide an introduction to Aquinas for modern readers, and who apply Aquinas’ ideas to modern problems. His personal favorites are the Thomistic philosophers Jacques Maritain and Étienne Gilson.

― Would you recommend people read Fides et ratio first?

― Yes, it’s a really good starting point. I found it to be a very enjoyable read and had trouble putting it down. It’s not overly long. It’s also a good counterpoint to Pope Francis’ encyclicals, because it is not focused on any one issue in the world or society. It is written at a very fundamental level.

Greg asks potential readers to remember that the encyclical is not like a novel, where you have to read from beginning to end. You are allowed to skip ahead if a point seems difficult to grasp and your attention begins to wander.

The encyclical Fides et ratio in Norwegian

Philosopher Richard Swinburne comments on Fides et ratio at the Angelicum in 2024